As part of his fight to win a confidence vote this week Boris Johnson reportedly told Conservative MPs that tax cuts where high on his agenda. How seriously should we take this?

The best answer is ‘not especially seriously’.

Fiscal Policy is already loosening.

To start with, it’s worth remembering that fiscal policy was already materially loosened two weeks ago. It is notable that the ‘tax cuts are coming’ noises are mostly emanating from Number Ten Downing Street rather than Number Eleven.

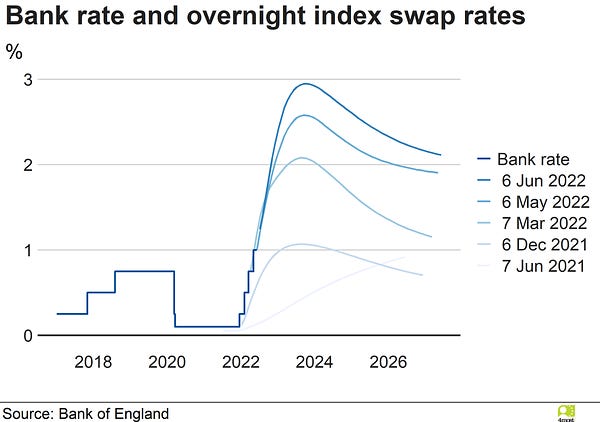

The UK’s macro-policy mix is looking somewhat healthier after the Chancellor’s latest intervention. More expansionary fiscal policy – and much better targeted at those set to experience the biggest falls in their real incomes – has given the Bank of England more space to engage in the kind of monetary tightening that they seem to think is necessary to keep inflation expectations anchored. Hopefully a combination of faster than previously expected monetary tightening with looser fiscal policy might even give sterling a bit of strength and help dampen imported inflation.

As I wrote before heading off on holiday (and any real sterling strength will have come too late for me), this new policy combination is probably better for overall growth and for inflation. But this kind of resetting of rate expectations:

… is hardly great news for the housing market.

From a straightforward macro-policy perspective the looser fiscal/tighter monetary mix looks clearly superior. But from a political-economy perspective - and keeping in mind the nature of the Conservative voting electoral block - the case is not clear cut.

We don’t know how much fiscal space the government has.

The problem with multi-billion-pound spending plans that are not accompanied by documents from the Office for Budget Responsibility is that it is hard to see how they fit into the government’s fiscal framework. The OBR’s forecasts are no more or less accurate than those of the Bank of England, or any other forecaster, but they play an outsized role in policy making. Ultimately, they have the final say on whether the government’s plans are consistent with their fiscal rules.

Before the Chancellor’s latest move, faster nominal GDP growth should have helped with higher VAT receipts and income tax revenue but increased debt interest costs and weaker consumer spending pushed in the other direction. The net outcome was likely a decrease in the Chancellor’s wiggle room consistent with the fiscal targets. Circa £15bn of new spending will now be added to that.

The Chancellor could, of course, simply change the fiscal rules. The UK has, after all, had around a dozen different flavours of fiscal frameworks in the last decade and a half.

But, so far at least, the Chancellor has been against this. He likes to talk of himself as both in favour of lower taxes and as a fiscal conservative. His actual record in office has involved hiking taxes to their highest share of GDP since the late 1940s and some of the largest peacetime deficits on record, but, when push comes to shove, he has tended to place lowering the deficit above cutting taxes.

Cutting public spending would be hard.

One way to square the circle would be to cut public spending and taxes at the time. But, despite Johnson’s recent noises about slicing the number of civil servants, that would be extremely difficult to achieve.

Not only after public services already struggling with a post-pandemic backlog but their cost pressures are already rising sharply. Recruitment is getting hard as private sector wage growth outpaces that of the public sector. Higher energy bills are hitting not just households and firms but schools and hospitals too.

I wrote a long-ish piece for the New Statesman on the Tories and tax a few months ago. In that I argued that it is important to understand the demographic changes that Britain has underwent since the 1980s and the changing composition of the Conservative’s electoral base.

Older voters have long skewed to the right in Britain, but the age divide has never been so extreme. Nor, until recently, did the underlying demographics of the electorate allow for a party to rely so heavily on older voters. In the mid-1980s, at the height of Thatcher’s electoral hegemony, those of pensionable age represented around 15 per cent of the population compared with around 20 per cent today. That share is forecast to rise towards 25 per cent by the mid-2030s. Differential turnouts by age magnify the impact. Margaret Thatcher won older voters but to retain power she needed to maintain the support of a substantial proportion of the working-age population; Boris Johnson has less need of them. Indeed, Labour led the Tories among the latter at the 2019 general election. The problem, for a party supposedly wedded to low taxes, is that older voters are rather keen on some types of government spending.

The Tories’ new electoral base – home-owning older voters who have either retired or are approaching retirement – have a different attitude to tax and spending from the Thatcherites of the 1980s. They may not like the notion of government spending in the abstract but they certainly do not want spending on the NHS, pensions or social care to be cut back. And such spending is an ever-larger part of Britain’s state. As the OBR noted last year, the overall size of the state is forecast to be around 42 per cent of GDP in 2024-25, strikingly similar to its pre-Thatcherite level in 1978-79. But while health, social care and pensioner welfare represented less than a quarter of government spending in 1979, they will account for more than a third by the mid-2020s.

There is structural upwards pressure on government spending coming from the aging of the population and it is among these older cohorts that government draws its key electoral support.

Would tax cuts actually help the government politically?

The implicit assumption of many Tory MPs is obviously to answer ‘yes’. And most people do prefer to pay less tax than more.

But in the current context it is questionable how much credit the government would actually receive from the public. The domestic annual energy price cap looks set to rise by something like £800 in October. A 1p cut in the basic rate of income tax (which some have suggested bringing forward to this Autumn) would slice the annual tax bill of someone earning £30,000 a year by about £175 a year.

Telling the voters that your actions are making them better off, even as their standard of living is squeezed, is not straight forward.

The longer term worry.

The bigger worry for the government though is surely the question of what happens next year.

As I wrote after the Chancellor’s statement:

This is the really big unanswered question. Implicit to the entire package is a belief that energy prices will fall in 2023. The government is extending extraordinary support to help households cope with, what is hopefully, a temporary period of high global energy prices.

But it is worth asking: what if prices stay high in 2023? Will the package be left in place? This is the kind of thing HMT civil servants will be worrying about this evening.

On the OBR’s, now hugely out of date, forecasts CPI inflation is set to fall to 4.0% in 2023. On the Bank of England’s more recent numbers have 2023 inflation averaging over 6%. Today’s OECD forecasts pencil in 7.4%.

It’s hard to see where the feel good factor is going to come from.

If you’re enjoying Value Added, please do subscribe. You’ll get more posts and I’ll get the resources to carry on producing it.