According to recent reporting, the Treasury is hoping that the cushion of savings built up by households over the course of the pandemic will be drawn down over the coming months to support consumer spending. That assumption is certainly implicit in the Office for Budget Responsibility’s forecasts for 2022 – which expect household consumption to power growth even whilst real household incomes take their biggest tumble in seven decades.

A sharp fall in the household savings ratio is certainly possible. I wrote more about household balance sheets, for subscribers, recently. But it is worth keeping in mind that the large rise in household bank balances – in aggregate – that occurred over the course of the pandemic was very unequally distributed. And that the households taking the biggest hit to their incomes this year – those that spend a greater proportion of their income on food and energy – are the least likely to have a high balance of savings to tap.

One side point to the increasingly reliance on private consumption as an engine of growth is the weakness of the other components of GDP.

Unsurprisingly, the bleak picture for household income dominated much of the discussion following the Spring Statement. But the expected weakness in business investment was almost as noteworthy.

In many ways the macro story of corporate Britain over the past two years is very similar to that of households.

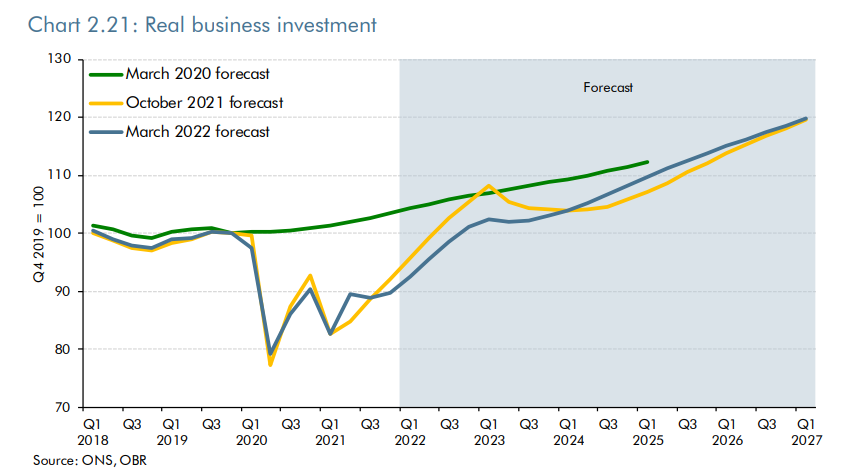

In March 2020, in a set of forecasts which were essentially ‘pre-pandemic’ (and therefore out of date almost before they were published), the OBR expected business investment to growth by around 10% between 2019 and 2024. That, in itself, would have been disappointing outcome. The Brexit-related uncertainty of 2016 to 2020 (when a deal with the EU was finally reached) had held back corporate investment. One would have hoped for some sort of catch-up eventually.

On the most recent forecasts, growth is expected to be just 6.5% over the same period.

This is despite the introduction of the temporary Super Deduction – one of the most generous tax treatments of capital spending of any advanced economy.

Initially the OBR – and many others, including me – had assumed that the tax break would pull forward some investment from the future. But take-up of the deduction appears to be much weaker than expected a year ago. As the OBR noted:

According to Deloitte, just 26 per cent of CFOs expected the super-deduction to have a positive effect on their investment plans over the next 12 months. Similarly, the CBI’s recent super-deduction survey found that of the 56 per cent of respondents planning to claim under the measure, only 19 per cent said this brought forward existing investment plans and 20 per cent said planned claims were for new investment that would not have taken place otherwise. The survey was also skewed towards those firms likely to use the super-deduction and each firm is likely to increase their investment by much less than 100 per cent given not all business investment is eligible for the measure.

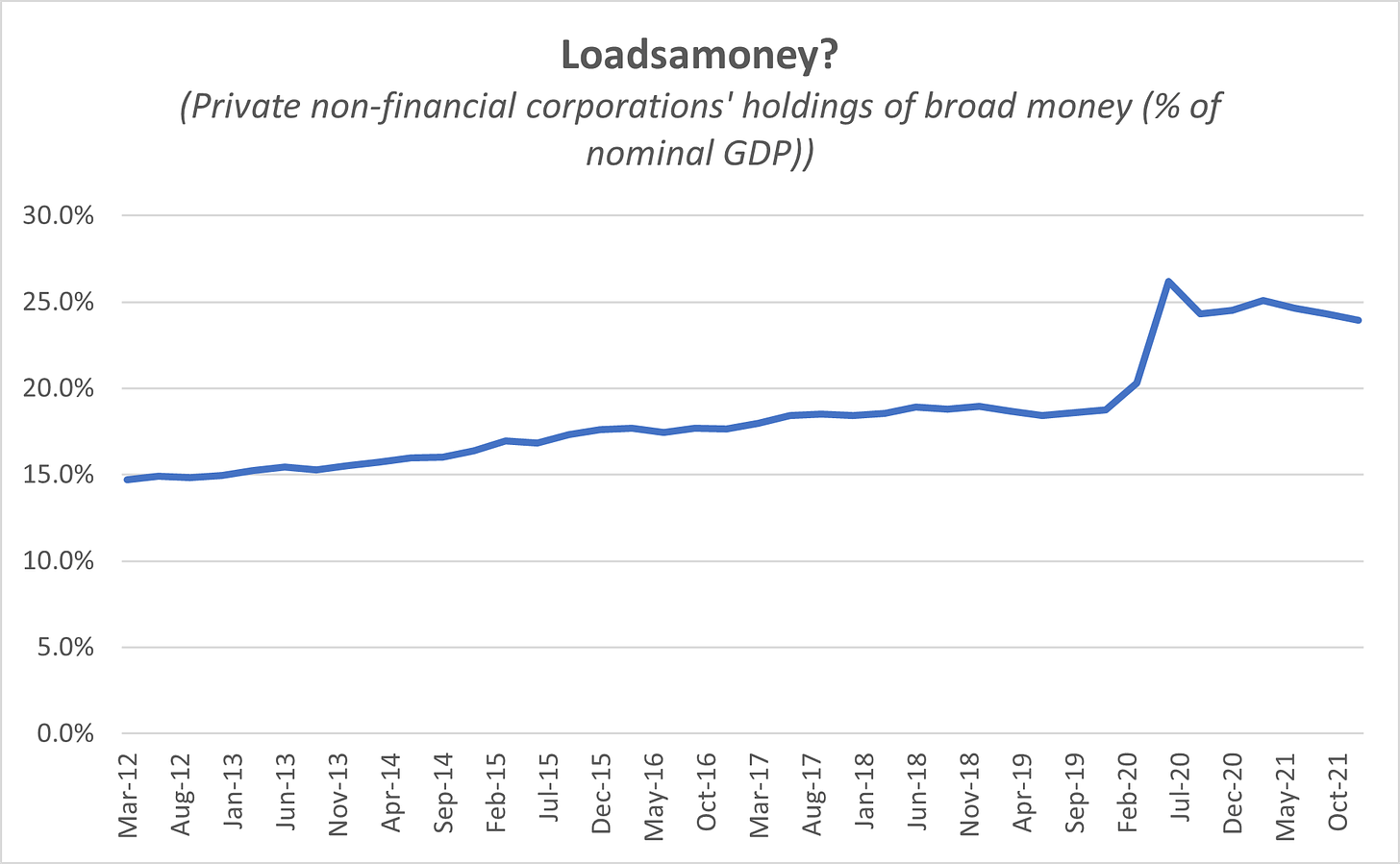

The weakness of business investment is especially frustrating given that, in aggregate at least, the sector is awash with cash.

The story of the pandemic for firms, at the macro level, is much like the story for households. The government absorbed much of the initial pain of the fall in output via tax cuts and loans and firms found themselves with surprisingly full bank accounts.

In theory, firms are sitting on excess cash worth around 5% of GDP compared to pre-pandemic norms. Easily enough to spur an investment book. But, again like households, the aggregate data does not tell the full story. The sectoral impact of the recession and the subsequent shifting patterns of consumer spending had a differing impact across corporate Britain.

Those cash levels are also partially the result of firms taking advantage of the cheap lending offered as part of the government’s support package.

The Bounceback loan scheme allowed small businesses to borrow up to £50,000 at essentially zero cost for the first 12 months and a minimal one afterwards with very little due diligence from the lenders due to the 100% government guarantee. Over two million such loans were issued, with a total value of £47bn. The existence of such generous support schemes has distorted the shape of corporate balance sheets.

This year supply chain disruption, vastly reduced government support, higher costs and weaker final demand will add-up to extremely tough trading conditions for many firms.

Concerns as the number of companies in critical financial distress increased to 1,891 in the first quarter of 2022, almost a fifth higher than the same period last year

The 19% year-on-year increase has been driven by a 51% jump in the construction sector and a 42% rise among bars and restaurants

Businesses in significant financial distress down 20% on the level a year ago at 581,596, though this is flat on the previous quarter

County Court Judgements – a warning sign of future insolvencies – up 157% to 22,552 in the quarter compared with a year ago; with March having seen the highest number in a single month for five years

Data from Begbies Traynor’s “Red Flag Alert” points to a coming wave of business failures as the economy adjusts to the post-pandemic reality with Covid reliefs cut off and a rapid growth in inflation (my emphasis)

Survival rather than investment will be the priority for many. Especially smaller, consumer facing, firms.

The macro-outlook for both British firms and British households this year are a useful reminder that aggregate numbers can only take you so far when trying to understand an economy. Superficially, households are sitting on a huge pile of savings to cushion this year’s squeeze in their income and firms, despite tough trading conditions, are awash with cash. But in both cases the distribution is extremely unequal.

If you are enjoying Value Added please do consider subscribing. You’ll get more posts and I’ll get the resources to carry on producing it.