It's all relative

Research from the BIS suggests that much of the recent increase in inflation is really a result of changing relative prices rather than a generalised rise. That has important implications for policy.

The Bank for International Settlements produces some of the most interesting macro research of any global institution. And whilst I don’t always agree with it, I usually find it interesting. This week the VoxEU write-up of a recent paper on inflation did what a good paper should do, it got me thinking.

Macroeconomics, as a discipline, has been having something of a crisis of confidence over its understanding of inflation in recent months. I’ve written before about Rudd and Goodhart’s worries that modern central banks lack a general theory of inflation. Jason Furman’s recent piece, asking why so few forecasters spotted the recent spike in inflation coming is well worth the time to read.

The paper from Borio, Disyatat, Xia and Zakrajsek is, perhaps, even more challenging. It starts from the premise that the spiking prices we are currently witnessing across the advanced economies are not really inflation at all, or at least not in a conventional macroeconomic sense.

True inflation, in macroeconomic theory, is a generalised rise in the price level. And a generalised rise in the price level is distinct from a series of idiosyncratic changes in relative prices. To give a concentrate example: a world in which energy prices quadruple is a world in which the headline rate of measured consumer price inflation would certainly rise sharply, but what would be happening would be the price of energy – relative to other goods and services – increasing rather than a generalised rise in prices.

Monetary policymakers are, of course, aware of this. One reason to focus on ‘core’ measures of inflation, stripping out often volatile components such as energy and food, is to allow them to judge to what extent any period of rising prices represents ‘true’ inflation and to try and concentrate on variables they can directly impact through changing monetary policy.

The new research from the BIS goes further. In their paper the authors, as they put it, “look under the hood” of inflation by breaking down the US PCE measure of inflation into 131 finely defined categories. That allows them to track ‘the common component’ of underlying price shifts. In other words, to go looking for generalised rises in prices rather than relative shifts.

Their results are stark. In the 1970s, the 1980s and into the early 1990s the common component was high. In the last couple of decades though, it has been very low.

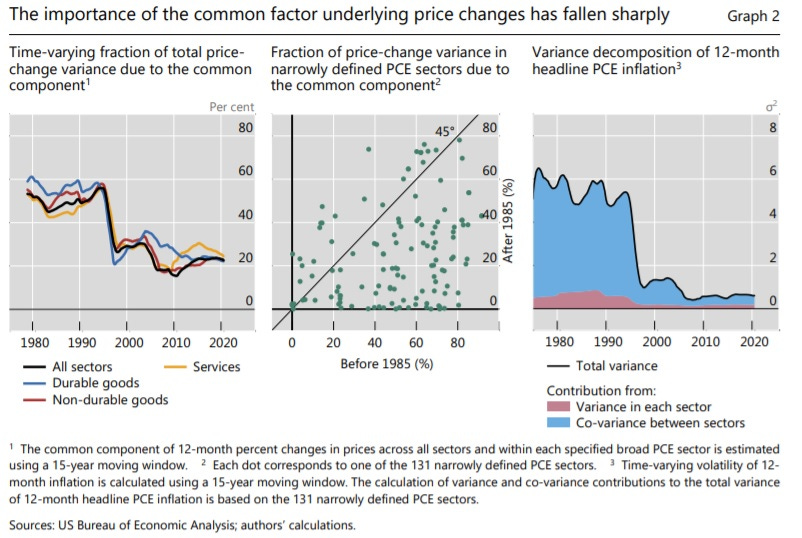

The fraction of the overall inflation variability attributable to the common inflation component drops sharply, from over 50% to between 15 and 30%, once the pre-1980 period of high and volatile inflation drops out of the estimation window (Graph 2, left-hand panel, black line). In fact, the decline is pervasive as it also applies to the rates of price changes measured at the level of the 131 expenditure sectors (middle panel). Moreover, the drop is also evident in both the trend and transitory components (not shown separately).

This leads the authors to conclude that the nature of the inflation regime under which the advanced economies operate has shifted fundamentally since the 1980s. Specific sectoral factors (changes in relative prices) now matter a great deal more than generalised, macroeconomic factors. Such factors aren’t entirely absent of course, they just matter much less than in the past.

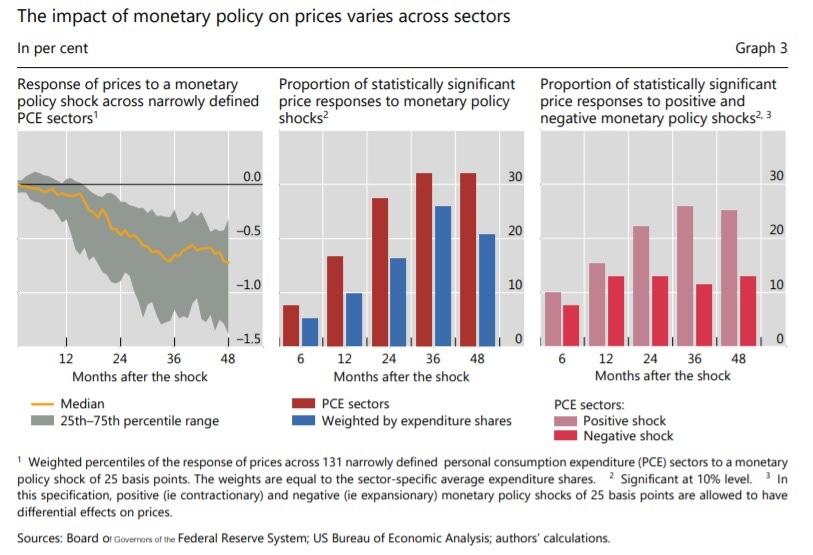

Furthermore, they find that monetary policy operates on a surprisingly narrow range of prices.

…it is striking that the impact on prices is statistically significant at conventional levels for only a small fraction of narrowly defined sectors – less than 20% at the 10% significance level after 12 months (Graph 3, centre panel). Even after 36 months, the fraction of sectors for which the price response is statistically significant rises to only about a third. Moreover, in terms of expenditure shares, the proportion is even lower across all horizons. In other words, the sectors whose prices are responsive to marginal adjustments in the stance of policy have a relatively small weight in the overall price index. Finally, the impact of monetary policy appears to be asymmetric: the fraction of sectors with statistically significant price responses is noticeably lower for expansionary monetary shocks across all horizons, compared with contractionary shocks (right-hand panel). Which sectors are relatively more responsive to changes in the policy stance? Not surprisingly, the bulk are in services, which on balance tend to be more sensitive to economic fluctuations ("cyclically sensitive"). (My emphasis)

Putting the two findings together: most of the ‘inflation’ of recent years – including the current bout – can be seen as sector specific changes in relative prices and monetary policy has much less impact than often supposed on these prices. Those are challenging conclusions for central bankers.

One can nitpick away at some of their arguments. For a start, the authors believe that the fundamental shift in the inflation regime was the result of a monetary policy shift in the 1980s:

The timing of the drop in its importance is quite telling: it coincides with the impact of the sharp monetary tightening in the late 1970s and early 1980s (the “Volcker shock”), in response to an inflation rate that was becoming increasingly unmoored.

Perhaps. But other stories – about changing labour markets, supply chains and globalisation are available.

More significantly, whilst I agree with the conclusion that central bankers should seek to show flexibility and look through shifts in relative prices…

these findings put a premium on flexibility in the pursuit of inflation targets. Since adjustments in the policy stance operate largely through aggregate demand – a common factor underlying all price changes – they may be less powerful once sector-specific price changes play a dominant role. When this factor affects a narrow set of prices, an overly forceful monetary policy action may be required to nudge overall inflation towards target, potentially causing undesirable shifts in relative prices. Flexibility can be especially important to reduce the potentially unwelcome side effects of the extraordinarily accommodative policy that may be needed to raise inflation back to narrowly defined targets.

… I am deeply uncomfortable with the final metaphor.

Put differently: just like a credible conductor of a well-rehearsed orchestra can afford to lead with minimal gestures, so a credible central bank can afford to let inflation evolve within a wider range of its target without energetic adjustments to the policy stance.

The central banker as conductor imagery – reminiscent of Greenspan as the Maestro – implies more control than is the case. Monetary policy is a powerful tool, but a hard one to wield with the kind of accuracy the metaphor implies. A Volcker shock type rapid tightening can crush demand and materially lower inflation - at the cost of a recession and higher unemployment. Extremely loose policy, if the circumstances align, can increase demand and add to inflation. But the notion that small adjustments in the policy stance can steer the economy with the precision of a conductor directing an orchestra has surely had its day?

If you’re enjoying Value Added please do consider subscribing. You’ll get more posts and I’ll get the resources to carry on producing it.

I was originally intending to increase the price of a subscription on January 1st (for new subscribers only, existing subscribers will stay at the same price they are already paying) but I forgot to schedule it decided to not immediately add to the cost-of-living squeeze. The price increase, for new subscribers, will now come in on the 1st February. So take advantage while you can.