Spring Statement Takeaways

An economic downgrade, a fiscal easing and some very odd policymaking

And, as the Chancellor rightly warned in his speech, the OBR were keen to note that these numbers do not yet take full account of the potential economic impact of the war in Ukraine and are all subject to higher than usual uncertainty.

For what it’s worth, the assumptions on consumer spending all look too bullish to me.

But the public finances are in a healthier state than the OBR anticipated at its last set of forecasts back in October. Largely due to faster than expected growth in tax receipts.

Relative to our October 2021 forecast, we have revised receipts up by £37.5 billion in 2021-22, by a slightly smaller £25.1 billion in 2022-23, and then by £28.8 billion a year on average between 2023-24 and 2026-27. In 2021-22, the upward revision reflects a large surplus in self-assessment (SA) receipts across income tax and capital gains tax (CGT), combined with stronger-than-expected outturns across corporation tax, PAYE income tax and NICs, and several other taxes.

Those higher than expected receipts gave the Chancellor wiggle room to ease policy whilst still hitting his own fiscal targets. The headline measures were a large rise in the threshold for paying national insurance contributions, a large one year cut in fuel duty and the pre-announcement of a cut in the basic rate of income tax in the last year of the Parliament.

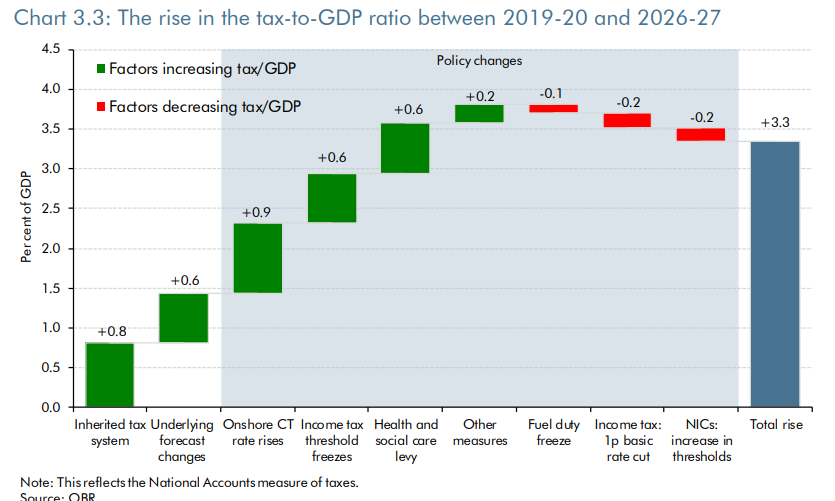

Still, for all of the Chancellor’s talk about his tax cutting credentials one needs to take this with a pinch of salt.

Over the course of the Parliament, taxes are heading up. Notably, the increase in national insurance contribution (NICS) thresholds is smaller than the amount raised by the new Health & Social Care Levy, whilst the giveaway from cutting the basic rate of income tax by 1p is smaller than the amount raised by the freeze in income tax thresholds.

Taken together, putting up national insurance rates (via the new Health and Social Care Levy) whilst cutting income tax amounts to a very odd tax policy.

In macro-policy terms, the fiscal easing announced since October should boost growth by around 0.3% in 2022-23 according to the OBR. Although within a context of fiscal tightening compared to the pandemic-related easing of 2020-22.

The large-scale fiscal support to households, firms, and public services provided during the first two years of the pandemic has now mostly been withdrawn. This support helped to keep unemployment and business failures low and to protect incomes from the drop in output caused by the pandemic, public health measures and voluntary social distancing. The withdrawal of support and net tax rises means the fiscal stance tightens in 2022-23 – though it is looser than in our October forecast thanks to new measures to support households in the face of higher energy prices. Further net tax rises (tempered somewhat by net tax cuts announced in this Spring Statement), partially offset by higher departmental spending, mean the fiscal stance tightens further in 2023-24 and 2024-25, and then remains broadly stable.

The contribution of discretionary fiscal policy measures announced since our October forecast, and incorporated in this forecast, loosens the fiscal stance in the near term and to a lesser extent in future years. These include measures to support households facing rising energy and fuel bills in the coming year (council tax and energy bill rebates, reductions in personal taxes via raising the NICs primary threshold, and a 5p cut to fuel duty) as well as a 1p cut in the basic rate of income tax that takes effect from April 2024. As described in Box 2.3, these measures raise real GDP by 0.3 per cent at their peak impact in 2022-23 and by more modest amounts thereafter – cushioning some of the near-term blow from higher energy prices.

Overall the measures announced today should cushion households - in aggregate - from around one third of the expected hit to real incomes coming from rising prices.

The combined impact of the energy-related support measures and tax cuts in 2022-23 boosts household disposable incomes by £17.6 billion. This reflects £350 worth of rebates for most households (£150 in April and £200 in October), the £6.3 billion NICs cut, and the 0.1 percentage point reduction in CPI inflation as a result of the temporary fuel duty cut. But as discussed in Box 2.5, real household disposable incomes still fall by around 2 per cent in 2022-23 – with the rebates and tax cuts reducing that fall by roughly 1 percentage point relative to no further support being provided, and thereby reducing the fall in real household disposable income by around a third. So the fall in real household disposable incomes in 2022-23 would be half as great again without these measures.

The ‘in aggregate’ matters here. Whilst the net fiscal giveaway is reasonably large it is not especially well-targeted.

And even with these measures in place, real household disposable spending is set to take a big hit.

The talk last Autumn of a new era of high wages and working bargaining power has not aged well.

The 5p cut in fuel duty, the increase in NICS thresholds and the promise of an income tax cut to come will no doubt get the Chancellor some favourable coverage in the days ahead. But as the squeeze on real incomes plays out in the months ahead it is hard to see the shine lasting for long.

If you’re enjoying Value Added please do think about subscribing. You’ll get more posts and I’ll get the resources to carry on producing it.