That '70s Show

2022 is going to be a painful year. But learning the wrong lessons would make it even more so.

The number of references to the 1970s appearing in economic opinion columns is stacking up.

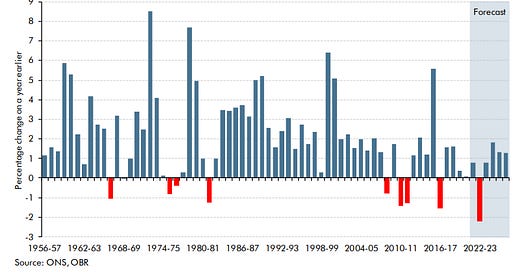

With British inflation at a 40 year and with growth beginning to slow, that is understandable. There is, after all, a word for the toxic combination of weak growth and fast price rises and one that is most associated with the 1970s.

Still, as readers of my book will know, I always think it is important to keep in the mind the unpleasant cocktail of factors that led to the high inflation of that decade.

Whilst it’s easy to point to the energy price and/or the wage-price as the major drivers, neither alone was sufficient. Instead one should take into account:

The energy price spike after the Yom Kippur War.

The wage-price spiral in the context of a radically different labour market and wage bargaining structure than exists today.

But also…

The end of Bretton Woods and the floating of a weak pound.

The newly liberalised/deregulated banking system and booming mortgage market.

The macroeconomic framework under which policymakers were analysing the economy and how it produced the wrong signals.

Some of the worst macro-policy making of the century, with the ill-timed dash for growth stoking the Barber Boom just as the energy crisis hit.

Pretty much everything that could go wrong on the inflation front, did. At the same time.

Yesterday, to remind myself of the US context, I found myself re-reading Brad Delong’s superb 1997 paper on the US experience.

I was especially struck by his argument that a period of high inflation was, perhaps, inevitable:

At a stretch, this can be expanded into a broader story of policy failures going back decades. Like generals fighting the last war, perhaps economic policy-makers fret over the last crisis. Seeking to avoid ‘another 1930s’ may have contributed to the soaring inflation of the 1970s and trying to avoid ‘another 1970s’, may have caused unnecessarily tight macro-policy in the decades afterwards.

It is worth remembering that for the current cohort of senior central bankers missing their inflation targets to the downside has been a much more pressing problem that missing them to the upside for at least the last decade.

Still, for the reasons I’ve outlined before, I don’t think the 2020s will see a repeat of the 1970s. I am still, just about, on what was once called team transitory. Energy and food prices may remain very high but are unlikely to rise at the kind of pace we saw over the last 12 months. Supply chains will eventually right themselves. Whilst domestically generated inflation has picked up, I worry more than slowing economies will weaken labour markets over the next year than about domestic cost pressures.

But the fact that inflation will (I hope) prove transitory is not much comfort for those seeing their incomes squeezed this year. I increasingly fear that 12-24 months of high inflation now will cause pain not just in the short term, but in the long run as well.

It is worth keeping in mind that, for all the dreadful associations it has amongst policy-makers, the 1970s did not see the kind of falls of household incomes that 2022 looks set to bring.

Across Europe, according to the latest EC forecasts, wage earners are set for an exceptionally painful year.

This sort of pain will have lasting consequence. As I wrote back in February:

Whether the current bout of inflation proves temporary or sustained, it is already changing the conventional wisdom.

The story of ‘aggressive fiscal and monetary policy prevented a depression’ is morphing into ‘aggressive fiscal and monetary policy lead to the highest inflation in three decades’.

Among policymakers the story of 2020 is already shifting. That view may soon filter out to the general (voting) public.

The counterfactual world, in which the fiscal and monetary response to covid-19 was materially smaller is a grim one. Inflation might well be lower but unemployment would be high. But people do not live in a counterfactual world, they live in the one we have.

For the next decade or more, the argument that ‘look we tried expansionary policy in 2020-21 and what happened? Inflation soared and everyone was poorer” will resonate politically.

2022 is going to a tough year for most people. If the lesson policymakers and the public take from it is that expansionary policy risks sky-high inflation, then the next recession will be a more painful time too.

If you’re enjoying Value Added, please do subscribe. You’ll get more posts and I’ll get the resources to carry on producing it.