The Bargaining Process

British wage bargaining is often poorly understood. That matters for the inflation outlook.

Wage bargaining will be key to next year’s British economic outlook and yet the actual mechanics of it are often poorly understood. While the current bout of above target inflation is mostly the result of global and pandemic related factors – high energy prices, disrupted supply chains and an unusual shift in consumer spending away from services and towards goods – some fear that it may prove more lasting by spilling out into domestic costs. The implicit, and sometimes explicit, assumption of many observers is that high inflation today may lead to higher wages resulting in higher inflation tomorrow.

The argument is usually that workers experiencing faster price rises now will anticipate higher inflation in the future and seek compensating rises in their own pay. That, in turn, will increase the cost base of firms and lead to them putting up their own prices to protect their margins. These are the basic mechanics of the old macroeconomic bogeyman that is a wage-price spiral.

People still tend to discuss this process as “wage bargaining”, although I worry that the phrase itself risks leaving people with a misguided notion of how the mechanism actually operates.

In the US context Jeremy Rudd, in his recent paper on inflation expectations, was wonderfully clear.

An observation about the actual nature of the “wage bargaining process” is helpful at this point. Outside of a few unionized industries (which now account for only about 6 percent of employment), a formal wage bargain—in the sense of a structured negotiation over pay rates for the coming year—doesn’t really exist anymore in the United States. In a world where most employment is “at will,” changes in the cost of living will enter nominal wages as part of an employer’s attempt to retain workers: If employers pay their workers a wage that falls too far behind the cost of living, they will start to see more quits, which will in turn force them to raise the wages they pay to existing workers (and those they offer to new hires). But there is no real scope for direct negotiation.

The same broad description generally holds for the UK.

The trade union picture on this side of the Atlantic is a little different. Union density is much higher at around 25% of employees. But what matters for wage bargaining, in the short term, is not so much density (the raw numbers of workers who are union members) but union coverage, that is to say the number of workers who have their terms, conditions and pay set as a result of union bargaining with employers. The latest British statistics put coverage at 25.6% of all employees, but with a heavy skew towards the public sector (57.2% of public employees being covered by collective bargaining) against the private (13.6%). That coverage level is about twice as high as the US (12.1% according to the OECD).

Public sector unions look set to face a tough pay round in the coming year with the Treasury keen to keep down costs. (A cynic might note that the Prime Minister eagerly talking up his new “high wage” economic model is hard to square with a government insisting that pay setting for its own staff should “have regard” to the Bank’s 2% target and guard against public pay rises that might spark more wage pressure in the private sector).

For seven out of eight private sector workers, the traditional mental model of organised collective wage bargaining is a relic of previous decades.

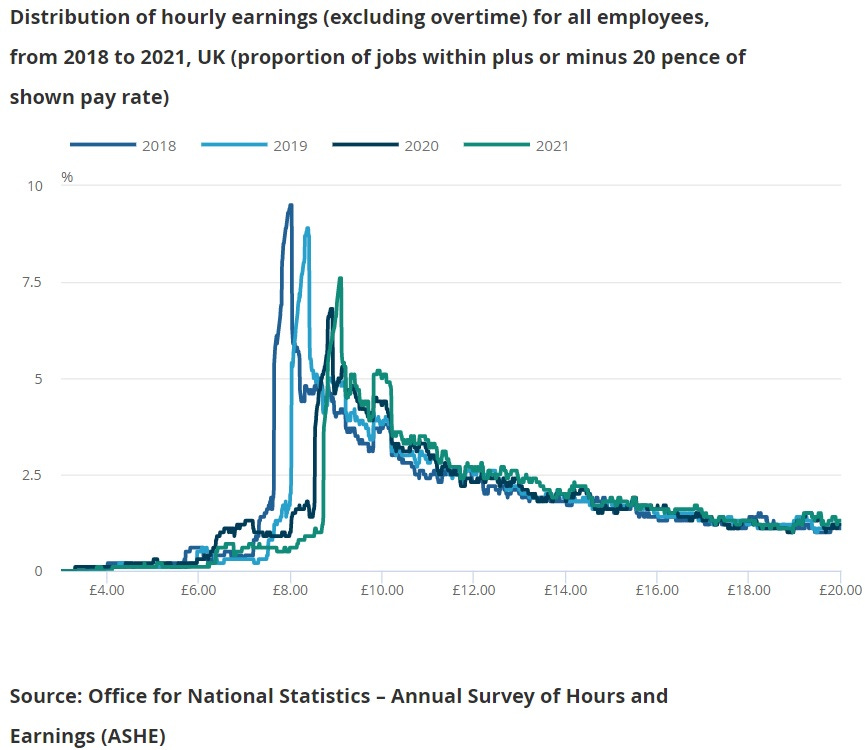

The minimum wage plays a larger role in Britain than America, especially since the punchy rises of recent years. The legal wage floor was worth 58% of median earnings in 2020 – up from under 50% in 2015 – one of the highest “bites” in the OECD and well above the 29% seen in the US. That high bite means that many workers earn something close to the wage floor and can expect to see their own pay increase whenever it ticks up as employers maintain differentials.

For much of low wage Britain, the government has a far more direct role in their own wage setting than any sort of bargaining process.

Rudd’s description of a model whereby “if employers pay their workers a wage that falls too far behind the cost of living, they will start to see more quits, which will in turn force them to raise the wages they pay to existing workers (and those they offer to new hires)” is a decent enough description of the UK too.

Indeed one reason for weak pay growth among younger workers in the post-2008 decade was that, contrary to the stereotype about flighty millennials constantly hopping jobs, 20-somethings did not change jobs enough.

The pandemic has given a short-term boost to this mechanism through a sectoral reallocation of labour. As the typical Briton has spent more cash on Amazon and other online deliveries and less on eating and drinking out, workers have shifted into sectors such as distribution and logistics.

This has almost certainly pushed up average pay in 2021 but represents a one-off change in levels rather than a sustained phenomenon. Workers leaving a minimum wage job to work in, say, an Amazon warehouse that has suddenly experienced record high demand and is hiring will see their pay jump from £8.91 an hour to £11.10 an hour, an increase of almost 25%. But it seems rather unlikely that distribution firms will be offering them a 25% pay rise next year.

To the extent that a strong jobs market gives workers more options to quit their job and find a new, higher paying, one then yes it can push up average wage levels and perhaps add to inflationary pressure. But one needs to exercise caution about how far that can really run in a highly liberalised system.

Take the British labour market of February 2020 on the eve of the pandemic as an example. The employment rate for 16 to 64 year olds was 76.6%, higher than today’s 75.5%. Unemployment was 4% against a current 4.2%. And yet nominal average weekly wage growth was running at just 2.8%. Few people were tearing out their hair worrying about a wage-price spiral.

This year’s wage numbers have been distorted by all sorts of compositional and base effects as well as rather too much anecdote-led reporting and too much focus on a handful of sub-sectors facing genuine shortages. The sectoral rotation of some workers as goods demand picked up has almost certainly pushed up the average level of wages to some extent but that is likely a one-off.

When people say “faced with higher inflation workers will bargain for higher wages” what they really mean in practice is “faced with higher inflation workers will look for alternative, higher payer jobs and either take them or use the offer of such a job to get a pay rise”. In other words what matters as a driver of wage growth is not so much the rate of inflation or some nebulous idea of inflation expectations but the overall health of the jobs market and the wider economy. And with a liberalised and flexible jobs market, as Britain has, it has to get very tight indeed before it generates sustained high earnings growth.

Over the coming months I’ll be doing what I’ve done throughout the recovery, watching the numbers produced by Indeed and staying relaxed about the prospects of a wage-price spiral.

If you’re enjoying Value Added – please do subscribe. You’ll get more posts and I’ll get the resources to carry on producing them.