The fiscal policy elephant in the room

The global macro debate is focussed on monetary policy. Fiscal policy will play a bigger role in the coming 12-18 months.

In the advanced economies the real policy action of the past 18 months has been on the fiscal side. Fiscal policy is set to tighten considerably in the months and quarters ahead. Yet much of the policy debate still seems to be mostly focussed on central banks.

Or at least that was my impression, so I decided to check if my intuition was correct by monitoring the daily barrage of emails from economic consultancies, sell side research firms and asset managers that landed in my inbox over my last six weeks working at the Economist. My priors, it seems, were not wrong: monetary policy got roughly five times as much airtime over the six-week sample.

There are of course perfectly understandable reasons for the usual skew towards monetary over fiscal policy analysis. For markets-focussed economists and strategists the direction of rates is the big question from which most other answers fall out. The fiscal policy stance is sometimes demoted to a mere input in trying to work out where monetary policy will end up.

And tracking monetary policy – and its likely direction – is a much more straight-forward process. If central bankers believe that inflation expectations are both a key determinant of inflation and the mechanism through which monetary policy is usually most effective, then they regard shaping such expectations as a key part of their job. So central banks produce policy reports, regular forecasts, research, working papers and a stream of often Delphic speeches to steer markets. By contrast few finance ministries produce anywhere near as much material and when they do it is often much more (explicitly) clouded in politics. And while the goals of monetary policy are, in theory, clear and focussed on a measurable metric such as inflation, the goals of fiscal policy are harder to pin down.

Monetary policy was certainly dramatic in 2020 but the fiscal response to the pandemic was even more so.

Bruegal’s snapshot on the scale of the advanced economy fiscal policy action by late 2020 is still eye-opening.

The “other liquidity/guarantee” part can be taken with a pinch of salt – in very few cases did the actual volume of government backed lending approach the scale of the facilities made available. In Britain the Chancellor offered a colossal £330bn loans facility but take-up was closer to £80bn (still, by any normal measure, a huge amount).

Developed market macro has been talking about “unconventional” monetary policy for so long that it is now almost conventional. The world in which monetary policy decisions consisted of nudging interest rates up or down feels a very long time ago. The story of 2020 and early 2021 was really one of unconventional fiscal policy – whether in the form of furlough and short time working schemes in Europe or of enhanced unemployment insurance in the US, coupled together with the kind of discretionary spending and tax breaks rarely seen in peacetime.

The best account of last year can be found in Adam Tooze’s Shutdown (which I reviewed for Prospect). My own reading of the events of the last 18 months, very much coloured by Tooze’s account, is that the shock developed economies suffered was extremely unusual not just in terms of the speed and severity of the falls in output but in just how much of the costs were, initially at least, absorbed by governments. Households and firms were shielded from much, but not all, of the impact by enormously expansionary fiscal programmes. Such fiscal programmes were aided and abetted by expansionary monetary policy which kept the cost of government debt issuance extremely low.

During the crisis, fiscal policy was not a mere input into the monetary policy decision making process – it was the primary channel through which policymakers sought to manage the cycle. Macro-policy worked because it was co-ordinated. But that co-ordination seems to be coming apart. And for all the focus on the monetary side of the equation, the real action is at the fiscal end.

Stepping back: interest rates are roughly the lowest they have been in five thousand years. They were roughly the lowest they had been in five thousand years five years ago and are still expected to be roughly the lowest they have been in five thousand years in five years’ time.

The fiscal picture is rather different.

The Brookings measure of the US fiscal impulse (pulling together Federal and state policies) is forecast to swing sharply negative after a dramatic expansion.

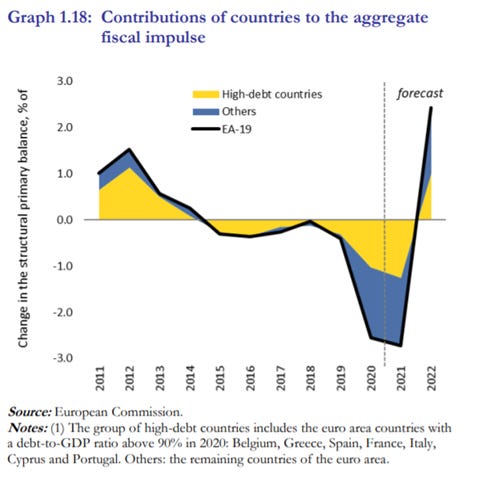

The European Fiscal Board is also forecasting an abrupt shift.

Note that while the US chart measures the contribution of fiscal policy to growth, and so shows expansionary fiscal policy as a positive number, the European chart measures the change in the structural primary budget balance and so shows contractionary fiscal measures as above zero. I’m sure one could write a lovely piece on what these charting decisions reveal about unconscientious biases.

The equivalent numbers for Britain are simply too abrupt to be real and will no doubt be revised at the coming budget later this month.

Monetary policy matters. But for all the attention is consumes, in the next 12-18 months fiscal policy – and the coming tightness – will play a larger role in the developed economy macro-outlook.

This post was free and, if you enjoyed, please do share it.

If you’re really enjoying Value Added (and hopefully finding that it does what it says on the tin and adds value) then please do consider subscribing. The first subscriber-only post is due this week.