Last week I wrote a guide to the readings I have found most helpful in understanding the effects on the war in Ukraine on the global macroeconomy. Part one focussed on the new sanctions regime and the impact on Russia, today’s continuation turns to the impact on the rest of the global economy. Later this week, part three will turn to what we don’t yet know: namely the macro-policy implications for central banks and finance ministries.

Food, Metals & Supply Chains

Russia, in purchasing power parity adjusted terms, makes up around 3% of global GDP while Ukraine’s share of global output is less than 0.5%. While Russia’s role in global energy markets is well known, it it is tempting to take some comfort from the small size of its share in wider global output and to assume that the macroeconomic consequences of its semi-closing will be contained. Sadly the lesson of 2020 and 2021 was that large global mechanisms often turn on small local parts.

Outside of energy the most immediate concern is in food supplies.

ING today published a helpful - if concerning - round-up of Russia and Ukraine’s role in the global grain market. As they note the problems run far beyond the closing of Black Sea ports by the war, there are growing concerns about Russian ‘self sanctioning’.

The issue with Russia which is concerning markets is the self- sanctioning we are seeing with Russian commodities. The risk of additional sanctions against Russia appears to have made buyers reluctant to commit to Russian supply. There is also likely an element of reputational risk at the moment for some buyers. In addition, banks are less willing to finance the trade in Russian commodities, which will further weigh on Russian supply making its way onto the global market. ..

In 2021/22 Russia is estimated to have produced 75.5mt of wheat, although has produced in excess of 85mt in recent years. Exports are estimated to total around 35mt this season, which would leave Russia as the largest exporting country, holding almost 17% of global export supply…

According to the latest data from the Ukrainian Agricultural ministry, cumulative wheat exports in the 2021/22 season stood at 17.96mt as of the 23 February. It is safe to assume that this number has not increased significantly since then. Given that exports were excepted to total 24mt this season, Ukraine still has about 25% to be exported between now and the end of June. This will be difficult given the ongoing conflict.

As ING note, the problem goes beyond grains.

…Ukraine is the largest sunflower seed producer, with the USDA estimating 2021/22 output of 17.5mt, which accounts for more than 30% of global output. It also has a large domestic crushing industry, of which sizeable volumes of both sunflower meal and oil are exported… Russia is also the second largest sunflower seed producer, making up 27% of global output. Like Ukraine, most of this will be processed domestically, and any exports are in the form of oil and meal.

To which one can add fertiliser. As Yara International, the leading European fertiliser firm, warned last week:

Russia has enormous resources in terms of nutrients. Plants need nitrogen, phosphate, and potash to grow. Nitrogen is supplied from ammonia, which is produced from nitrogen from air and natural gas. The importance of gas has been on the agenda in the debate around the high European gas prices in 2021 and beginning of 2022. 40% of the European gas supply is currently coming from Russia. With regards to potash (a salt extracted from clay deposits), the market is highly concentrated and fragile towards change. Today, 70% of extracted potash and 80% of all exported comes from Canada (40%), Belarus (20%) and Russia (19%). In total, 25% of European supply of these three nutrients come from Russia.

The FT’s use of the phrase ‘food crisis’ its analysis is sadly not hyperbole.

Soaring food prices are painful everywhere, but especially so in less advanced economies where food makes up a larger share of household spending.

Key agricultural commodity prices are now at the sort of levels last seen around the time of the Arab Spring.

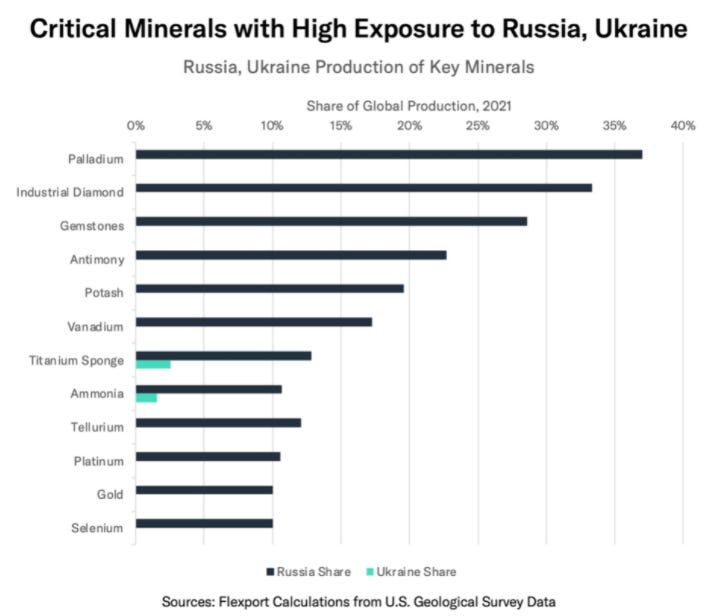

Aside from food and energy, supply chain experts are fretting over metals. A rundown last week from Reuters shows that Russia has sizeable global market shares in steel, copper, nickel and aluminium together with 15% of the global supply of titanium and around 40% of the global supply of palladium - both of which are crucial inputs for the aerospace industry.

Flexport have a handy list of key minerals with large Russian/Ukrainian market shares.

Then there the wider impact of the effective closure of Russian airspace on goods that have little to do with Russia itself. Marketwatch published a useful run through:

…flights originating in Europe or Asia that previously travelled over Russia will need to reroute, which can add hours to the travel time. That necessitates more jet fuel — which not only adds to the cost of each flight for the airline, but also reduces the amount of cargo that can be carried on each aircraft due to weight considerations. Those costs will likely be passed on to the consumer.

The delays and costs involved for general air freight are unwelcome but manageable. A larger problem is being faced by users requiring air transport for especially heavy and bulky cargo. In this more niche market (moving things like jet engines), Russian and Ukrainian shippers play an outsized role.

The primary losers are shippers with heavyweight and outsize cargo that don’t fit well in regular cargo jets. Ukraine-based Antonov Airlines is continuing some operations with five AN-124 super-jumbo jets, but two of the aircraft plus a smaller freighter were not able to escape before hostilities erupted. And the company’s behemoth AN-225, which was undergoing repairs, was reportedly destroyed last weekend.

Western companies also have lost access to Russian cargo specialist Volga-Dnepr, which operates a dozen AN-124s and five Ilyushin-76 freighters, and its Boeing 747-dominated subsidiary AirBridgeCargo because of airspace and banking sanctions against Russian companies.

The large airlifters were increasingly busy hauling general cargoes during the pandemic because of the overall shortfall in transport capacity and because Volga-Dnepr and Antonov Airlines offered below-market rates in many cases.

Energy

The energy shock is the one dominating the news agenda and the market where the pressure for a tougher sanctions regime on Russia is the most acute.

This sort of chart certainly grabs one’s attention.

As does this sort of oil pricing.

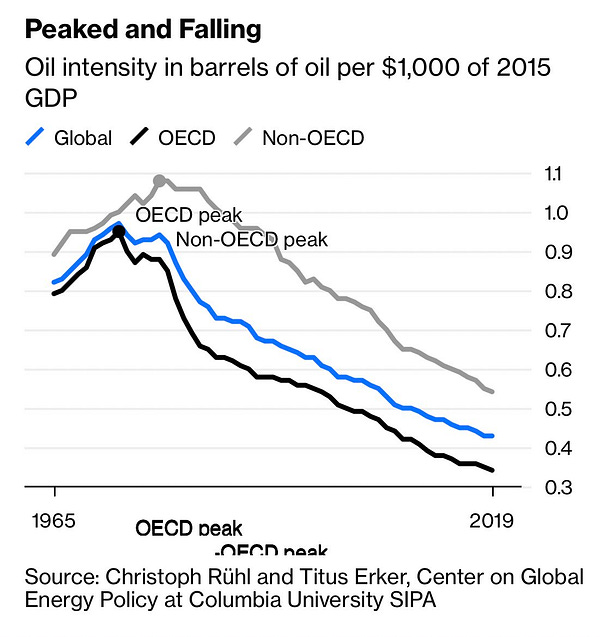

The good news is that the global energy intensity of GDP is much lower than the in 1970s:

But the bad news is the price ramps of the kind seen in recent days are still of an order of magnitude big enough to cause a very nasty economic shock.

The discussion of energy markets in last week’s the Bottom Line with Greg Jackson of Octopus Energy (from about 15.45 minutes in) was very useful.

Greg’s general sense of the global gas market - that Europe will take less Russian gas and China will take more, freeing up Asian and Australian LNG supplies for Europe - still implies high and volatile prices for the months ahead.

For all the reduced energy intensity of GDP, an energy price shock of the magnitude currently being experienced means a meaningful hit to consumer real incomes and a fall in industrial production.

What about an actual cutting off of Russian gas supplies? A very timely paper from the ECB - published just three weeks ago - offers some clues:

Regarding supply disruptions, the direct and indirect impact of a hypothetical 10% gas rationing shock on the corporate sector is estimated to reduce euro area gross value added by about 0.7%.

I.e. a 10% immediate drop in gas supplies (if not replaced) would reduce Euro-area GDP by 0.7%. With the impact varying across countries due to the sectoral and energy usage mixes.

There is no doubt that the global economy faces a hit to output and higher inflation as a result of the war in Ukraine. The magnitude of both is unknowable, too much depends on the course of the war and in particular how long it lasts, what any peace looks like and whether sanctions or Russian economic retaliation escalate further.

Later this week, I’ll turn to how central banks and finance ministries will respond. For central banks in particular, the risk of a policy mistake is rising.

If you’re enjoying Value Added please do consider subscribing. You’ll get more posts and I’ll get the resources to carry on producing it.