Britain's macro-policy mix is a mess

Over the coming 12-18 months fiscal policy will matter more than monetary policy in Britain. Political economy is trumping macroeconomics and driving the Chancellor to over-tighten.

For all the attention being paid to the Bank of England, the big UK macro-policy event of the next 6 months is happening this Wednesday, and it is coming from the Chancellor rather than the Monetary Policy Committee.

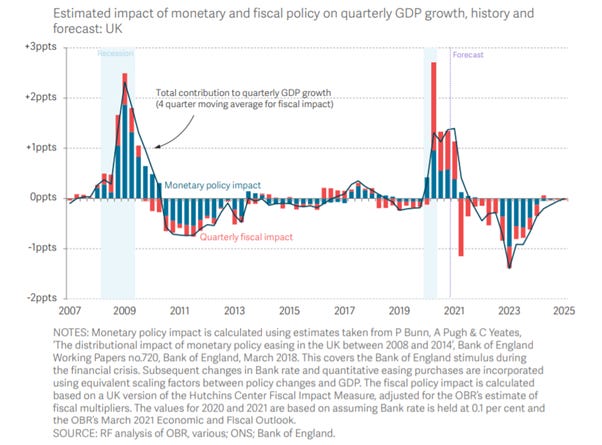

As the Resolution Foundation have pointed out, in a truly excellent chart, over the coming 12-18 months the real policy action is all expected on the fiscal side.

Despite the weakening of the pace of the recovery over the past few months, the Chancellor should have a good story on Budget Day. The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR)’s current forecasts look increasingly pessimistic. That is hardly their fault – they closed the last forecast round in late February at a time when the success of the vaccine rollout was far from certain.

GDP growth in 2021 is likely to be closer to 7% than the 4% pencilled-in back in March.

Borrowing this financial year should undershoot the March forecast by around £30bn.

More significantly for the medium-term public finances, the OBR’s estimate of the long-term scarring from covid-19 being worth around 3% of GDP is now seriously out of line with other forecasters. The Bank of England believes the long-term hit will be closer to 1% of GDP.

Pushing in the other direction, inflation will be materially higher than expected at the start of the fiscal year. Still, the underlying fiscal numbers will be much healthier than expected seven months ago.

While the Chancellor could, in theory, use these improved forecasts as an opportunity to ease fiscal policy that seems very unlikely.

While Sunak was a big spending during the pandemic (something which has certainly helped his own popularity among the general public) his instincts on fiscal policy in general are far more hawkish. That has been very clear this Autumn. The cut to Universal Credit as the temporary pandemic-related £20 a week uplift was allowed to expire was not the action of a fiscal dove. Nor was his insistence that the bill for clearing the pandemic-related NHS backlog would be met through a rise in national insurance contributions rather than additional borrowing1.

All of which raises two questions. What is behind the coming tight fiscal policy? And where does this leave UK macro-policy in general?

The forecast rapid tightening in fiscal policy (which is expected to be noticeably more rapid than the US or European approach in the months ahead) is more of a political economy story than a macroeconomic one. Although it will certainly have macroeconomic implications.

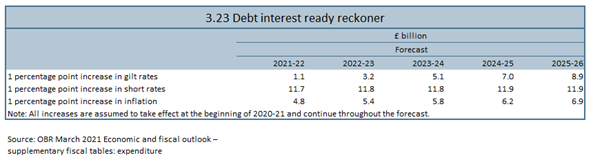

The Chancellor’s favourite statistic to justify it, and one that will no doubt be trotted out in tomorrow’s speech, is the idea that a one percentage point rise in inflation and interest rates would increase the government’s interest bill by £25bn. This, according to the Chancellor’s supporters, justifies rapid action to close the deficit.

Those figures come from the OBR’s ready reckoner but are, at best, a partial rendition of the full picture.

The first thing to note is that the single largest driver of the increased interest bill comes not from gilt yields or inflation but from a rise in short rates. This is a mechanical side effect of QE, as set out in a speech earlier this summer from Gertjan Vlieghe. QE, as it currently operates in the UK, leaves the government more exposed to short rates than in the past as around a third of the stock of government debt is held by the Bank and effectively paying Bank Rate.

…the net effect of QE can be thought of as akin to swapping the cost of part of the government debt from long-term interest rates to short-term interest rates (the rate paid on reserves, i.e. Bank Rate)… That works in both directions. When short-term interest rates are low, as they have been for the past decade, the interest cost faced by the government is also very low. Bank Rate has been below the yield on most gilts for the past decade. But if Bank Rate rises, the interest cost faced by the government will immediately rise, one for one, on the portion of government debt that is held by the Bank of England, which is roughly equal to the amount of reserves outstanding. That is in contrast to the more gradual pass-through of interest rises on the portion of government debt that is held by the private sector, where interest rate costs only rise at the pace at which bonds mature and need to be refinanced.

This is all mechanically true at present but needs to be taken with a pinch of salt. For a start, the Bank could always introduce ECB or Bank of Japan style tiering on reserves to sidestep this issue.

More generally, the Bank (whatever may be implied by markets which are getting ahead of themselves) is very unlikely increase Bank rate by one percentage point over the coming year.

Even if Bank Rate were to rise by one percentage point and the government’s interest bill did indeed increase by the oft repeated figure £25bn that is still only looking at one side of the ledger. Presumably in a world of higher rates and inflation, tax revenues would also look perkier too.

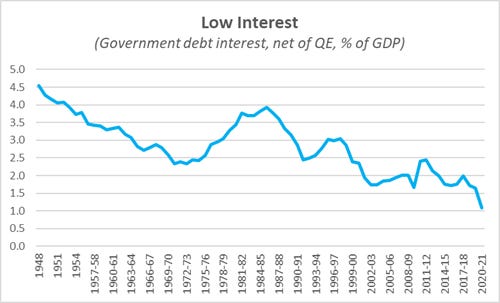

And, it bears constantly repeating, the government’s interest bill is currently at historically extremely low levels.

In other words, the UK’s debt dynamics do not appear to be about to spiral out of control. The coming fiscal tightening is discretionary, and the driver is more politics than economics.

Partially this is a straightforward story of a Chancellor doing what Chancellor’s are wont to do and running tighter policy in the short term to build fiscal space for looser policy heading into an election. And partially this is a story of a Chancellor who wants to maintain a political dividing line with the Labour opposition by insisting his party remains “the party of low borrowing and fiscal rectitude”.

But, worryingly for the wider UK macro-policy mix, I fear it is something deeper than that.

One of the odder features of British political economy over the last decade is the transformation in how politicians talk about interest rates. Interest rates are, in a standard macro framework, a tool of policy – something which are lowered or raised to hit wider policy goals be that fuller employment or more stable inflation.

But since the turn of the millennium there has been an increasing tendency among fiscal policymakers to treat low interest rates as a goal in and of itself. Labour’s re-election posters in 2005 boosted of “the lowest interest rates in decades” whilst George Osborne as Chancellor from 2010 to 2016 regularly cited the need to keep interest rates low as a justification for tight fiscal policy.

In a world in which homeowners hold disproportionate political power, then such talk makes political sense if even it holds little economic logic. Lower interest rates, all things being equal, mean higher house prices. A monetary tightening cycle has the potential to knock house prices.

The worry now is that British fiscal policy is being set unnecessarily tight – partially to create political dividing lines and a pre-election war chest and partially in an effort to head-off the Bank of England’s hawkish turn. Fiscal policy space is being traded for monetary policy space at a time when much macro theory suggests fiscal policy is at its most powerful.

If you’re enjoying Value Added please do subscribe. You’ll get more posts and I’ll get the resources to carry on producing it.

The new Health and Social Care levy has been sold as “paying for social care” but, for the rest of this Parliament (at least) the majority of the funds raised have been earmarked for the NHS.