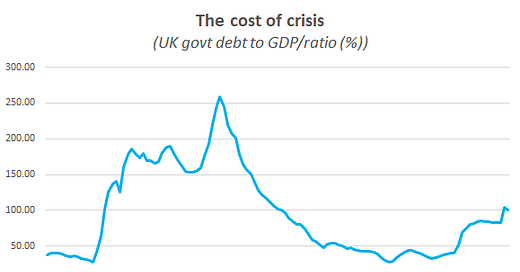

Fifteen years ago Britain’s government debt to GDP ratio stood at around 40%. Today, after a financial crisis, a pandemic and two recessions, it stands at around 100%.

The chart of that ratio - and how it moved over the course of the twentieth century - is a familiar one.

Wars, pandemics and financial crises are costly things. And the post-financial crisis/pandemic debt spike is comparable to the debt spikes seen in the two total wars of the twentieth century. Indeed, the borrowing numbers the Treasury wracked up in 2020-21, as measured against GDP, were the highest ever seen in peacetime and closer to the early 1940s than any other period in modern British economic history. Whilst I am writing this piece with reference to Britain, the broader lessons apply across many advanced economies.

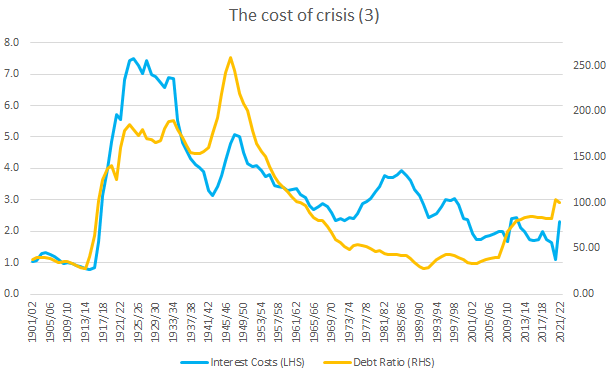

Less familiar than it should be is another chart. This one is too deals with the costs of disasters but looks at it from another angle: the interest costs incurred by the government.

The pictures presented by these two charts are strikingly different. Putting the two together rams the point home.

The surge in debt associated with the First World War was accompanied by soaring interest costs. More than 7% of national income was being devoted to servicing the government’s borrowings in the early 1920s. By contrast the larger increase in the size of the national debt that came about during the Second World War was accompanied with a lower burden as measured by the cost of servicing it.

From the day to day perspectives of finance ministries and taxpayers it is servicing costs - rather than the total actually borrowed - that really matter. The burden of debt is a matter of interest rates as much as grand totals.

So what now?

This all feels very relevant at the current juncture. The stock of government debt has increased substantially but whether or not the cost of serving that debt follows the same path is not clear cut.

Central banks are clearly - Japan aside - in tightening mode. And as policy rates rise, that will feed through into the borrowing costs of governments.

Normally that process would operate at a lag, with higher short term rates only impacting the government interest bill as debts come due and are refinanced.

Quantitative easing has complicated the picture. My very smart ex-colleague, the Economist’s Henry Curr, has been pointing this out for quite some time. This week he is back on the topic arguing that across the advanced economies the maturity of government debt is lower than the headline statistics suggest and that interest bills will be rising quicker than in the past.

Gertjan Vlieghe set out the mechanism though which this could occur clearly in a speech last year. For most of the last decade QE has reduced the costs of government debt both indirectly - by lowering longer term interest rates - and through a more direct mechanism. The effective cost to the Treasury of any debt held by the Bank is simply the payments on Bank reserves. As the Bank has remitted the net interest payments back to the Government, it doesn’t matter whether the underlying gilts purchased by the Bank were yielding 2%, 3% or 4% - the Treasury was effectively paying Bank Rate which, for most of the last 13 years has been 0.5% or under.

But as Bank Rate rises - and hence the interest paid on reserves held at the BOE rises too - then so does the government’s interest bill. QE can, on one level, be thought of as a maturity transformation in the government’s debt, effectively transforming much longer term borrowing into shorter term liabilities. Given that short term interest rates have been at historical lows for most of QE’s existence this reduced the cost of servicing government debt for most of the last 15 years but now leaves the government more exposed rising short term rates than in the past.

This is the logic behind the Office for Budget Responsibility’s warning that each one percentage point increase in Bank Rate will add 0.5% of GDP to Britain’s debt serving costs within a year.

But it doesn’t have to be like this. Mechanisms can be changed. Indeed both the National Institute for Economic and Social Research and the New Economics Foundation have proposed changes to how the Bank operates to break the mechanism. Tony Yates and Toby Nangle assessed those plans for Alphaville recently.

Lord Turner and Karl Whelan have both, along the lines of the NEF and NIESR reports, suggested that central banks such as the BOE could introduce a tiering system whereby most of the reserves held would be paid no renumeration.

Back to the history.

Britain experienced two major spikes in government debt in the twentieth century and it handled them very differently1.

For more than a decade after the Great War the authorities attempted to handle the debt in an entirely conventional manner - running a tight fiscal policy with large primary surpluses. The tax burden rose sharply and public spending was subject to the Geddes Axe. The results were disastrous.

Not only did Britain experience a truly grim 1920s in terms of weak growth and high unemployment but the government, despite the debt-focus, failed to reduce the debt ratio.

The financing of the next war and the subsequent decades were rather different. This time the policy was what has come to be known as financial repression. In short, the use of prudential and regulatory powers to force the financial sector to hold debt at lower interest rates than the market alone would dictate.

Britain was far from unique in this:

After WWII, capital controls and regulatory restrictions created a captive audience for government debt, limiting tax-base erosion. Financial repression is most successful in liquidating debt when accompanied by inflation. For the advanced economies, real interest rates were negative ½ of the time during 1945–1980. Average annual interest expense savings for a 12—country sample range from about 1 to 5 percent of GDP for the full 1945–1980 period.

Britain’s post-Second World War economic performance was far from perfect2 but on just about any measure it was reams ahead of that after the Great War. Employment was higher, growth faster, living standards rose quicker and the debt to GDP ratio was reduced at a much faster rate.

In 1919 Britain’s debt ratio stood at 140%. Twenty years after the First World War in 1939 it was over 150%. In 1945 it was around 240%, twenty years later in 1965 it was 85%.

An economic history hill I am prepared to die on would be that “financial repression sounds like a bad thing, we should rename it ‘historically normal and successful debt management policies’”.

Financial repression is far from a cost-free option3 as the Economist noted this week:

Using tiering to avoid paying banks interest while their funding costs went up would be a tax in disguise. Banks, considered together, have no choice but to hold the reserves QE has force-fed into the system. Compelling them to do it for nothing would be a form of financial repression which may impair banks’ ability to lend. It would “transfer the costs [of rising rates] to the banking sector,” Sir Paul Tucker, a former deputy governor of the Bank of England, told parliament in 2021.

But taking a conventional approach to the management and serving of government debt is not cost-free either.

The appropriate policy stance at present is looser fiscal policy - targeted at shielding households and firms from higher energy bills - coupled with tighter monetary policy. That combination though - as QE currently operates in Britain - would mean a large spike in government debt service costs. Possibly one large enough to deter the Chancellor - whoever that happens to be by this Autumn - from taking the necessary steps.

Macroeconomic policy is usually about trade-offs. The consequences of a spike in government debt are no different. Presented with the examples of the handling of the two previous debt spikes, I know which one I prefer.

Thanks for reading Value Added. It is a subscriber funded publication. If you’re enjoying it please do consider taking out a subscription. You’ll get more posts and I’ll get the resources to carry on writing it.

There was also a major debt spike in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, again associated with war - this time the American War of Independence and the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. For the super-interested, how that debt was dealt with is the subject of a lengthy section of my book. But unless one thinks that the UK is heading back to the days of a ultra-minimal nightwatchman state, then I fail to see any relevance to the current macro debate.

For American readers, please consider this sentence an example of British understatement.

Especially given changing demographics and the questions around pension saving.