Does the Bank of England believe its own forecasts?

The Bank's actions are hard to square with its numbers. Plus: some free advice for the Governor.

Value Added had an unexpected interruption in service last week as I spent much of it in bed with a high, but not-covid related, temperature. Apologies.

But no matter how bad my week was, I suppose it could have worse. At least I didn’t spend it in the Bank of England’s press office.

Later this week I’m going to turn back to the question of central bank communications. But it would be impossible to write anything about the Bank of England this week without, briefly, mentioning that interview.

I can’t remember another occasion on which both the FT and the Daily Star have led with the same story.

For what it’s worth, my media training advice would be: ‘if the journalist looks genuinely surprised and asks ‘really?’, that should be taken to mean ‘you have dropped a massive clanger here and I am giving you a chance to walk away from it’’.

What makes the comment even more inexplicable is the general picture emerging from the data is the rate of nominal wage growth seems to have peaked anyway.

But more on all this later in the week.

Today, it feels worth pausing to note just how unusual this hiking cycle really is. Of course, everything is unusual now. The pandemic has warped the business cycle into a strange sort of shape that makes any comparison with previous cycles far from straight forward. We currently have the odd spectacle of real household incomes, which held up pretty well during a deep recession, falling in the early stages of the recovery. And now of a monetary policy hiking cycle that is just getting underway as momentum in the labour market seems to be peaking. Strange times indeed.

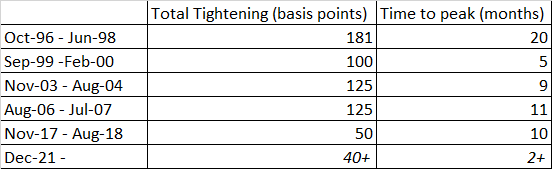

To get a sense of just how unusual, it is worth looking back at the previous hiking cycles. The Bank adopted inflation targeting in October 1992 and gained its operational independence in 1997. The table below looks at the five post-independence cycles that have occurred over the last 25 or so years (the first of which began during the tail end of the ‘inflation targeting but not yet independent’ period).

The last cycle before the present one would probably had further to run if the pandemic had not intervened. But even so, it stands out has unusually shallow.

A typical hiking cycle for the Bank takes around a year (the average of the previous cycles has been 11 months) and delivers 100-125 basis points of tightening (average of 116).

It is clear that the current cycle is not going to reassemble that of 2017-18, at least when it comes to the pace of hikes. It is already moving faster than the languid days of the late 2010s and much more in keeping with that of earlier cycles.

What is very different is the starting point. (A reminder: the Bank targeted RPI less mortgage interest payments (RPIX) of 2.5% until 2003, and then CPI of 2% after that).

The Bank, in its inflation targeting incarnation, has never begun a cycle so far from target.

Of course, the MPC would respond, they do not target current inflation but the likely rate of inflation in two years’ time. Monetary policy operates with a lag.

That though just raises more questions. Because the Bank’s own forecasts do not suggest inflation, in the timeframe under which monetary policy operates, is especially threatening.

On the MPC’s own numbers, rates at 0.5% should return inflation to target over the course of the forecast period (the right-hand chart), whilst following the path implied by market expectations would see inflation more likely to undershoot (the left-hand chart).

Squaring these forecasts with four votes for additional tightening now, the committee as a whole noting the need for “further modest tightening” in “the coming months” and the general reluctance of MPC members to push back against market expectations is very difficult indeed.

It leads to two possible explanations. Either some members of the MPC, whatever they might profess, are indeed responding to current inflation when voting for hikes or, more likely, their level of confidence in the forecasts is unusually low. That is perhaps understandable given the persistent overshoots of inflation, relative to the BOE’s forecasts, over the past 9-12 months.

The Monetary Policy Committee having a lower than normal level of confidence in their own forecasts might be understandable but it is hardly reassuring.

If you’re enjoying Value Added please do consider subscribing. You’ll get more posts and I’ll get the resources to carry on producing it.