Value Added Round Up

Inflation, good/bad job market news, whither the OBR?

That inflation release

… was bad news. It’s quite hard to sugar-coat it. Both headline and core readings came in ahead of expectations.

Analysts have their own preferred ways of cutting the data, but sometimes a really simple approach is all one needs. And it doesn’t get much more straightforward than just looking at service and goods price inflation.

To over-simplify - but not by much - goods prices are generally more volatile and more impacted by global factors. Services prices are more stable and, in the main, reflect domestic factors.

Once upon a time, in the NICE decade before 2008, British service price inflation was about 4%, broadly in line with average earnings growth and goods prices were falling, keeping overall inflation around about the 2% target.

In the 2010s service price inflation was materially weaker, reflecting a decade of weak nominal wage and productivity growth.

The Bank, in general, has usually been happy to look through goods price inflation. But services price inflation running at a 30 year high is the kind of thing that prompts it to do unpleasant things such as hiking into a recession.

Good news and bad news in the jobs market

We’ve entered one of those phases when it is hard to whether the exact same trend is good news or bad news. This week’s jobs figures are a case in point.

I was very struck by the BOE’s approach to looking at labour supply and demand in their most recent forecasts.

The Bank - and I think this is the part of their forecast most likely to prove incorrect - expect the tightness in the jobs market to last well into 2023. I’m less sure.

This week’s stats then, which show some signs of the tightness fading can be taken as either bad news for workers or good news for inflation prospects.

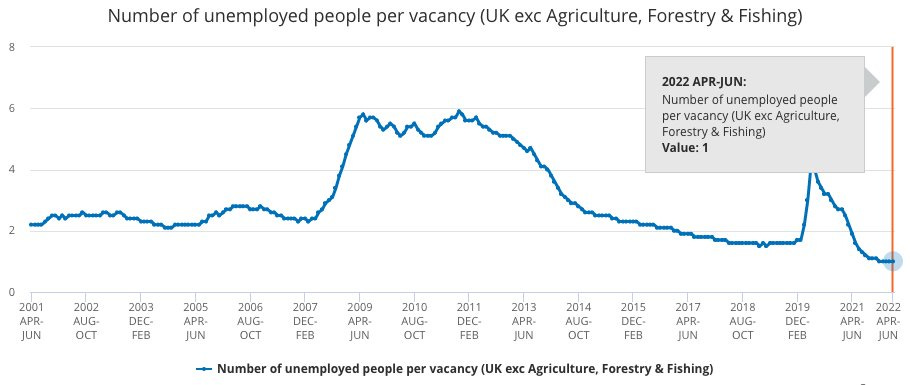

On the labour demand side, vacancies remain elevated but there are clearly signs that the mismatch between job ads and unemployed workers has at least stabilised.

Indeed’s data has vacancies about 4% off their peak.

I rather suspect that a combination of higher business energy bills and weaker consumer spending will cause many hiring plans to be revisited in the months ahead. I struggle to see labour demand staying as high as it has been in recent months.

On the labour supply front, Samuel Tombs spotted some reassuring news on non-British born workers.

Equally interesting is the rise in the 65+ employment rate.

Some of this no doubt reflects the state pension age rising to 66 in October 2020 but we may also be seeing the start of a trend of ‘unretirement’. As the Bank put it in the latest Monetary Policy Report:

Firms have reported to the Bank’s Agents that some of their employees have reconsidered their plans during the pandemic and taken early retirement. According to Labour Force Survey (LFS) data on reasons for inactivity, this channel is fairly small relative to other factors (Chart 3.6). Data on labour market flows which capture the characteristics of people changing labour market status suggest a larger role for early retirement in explaining the pickup in inactivity (IFS (2022). But these data have a smaller sample size than the headline LFS measures.

I heard the same form many firms during the pandemic, a proportion of workers in their late 50s or 60s reassessed how they were spending their time - often whilst on furlough - and retired earlier than planned.

But retirement plans made in late 2020 or when furlough finally wound down in late 2021 almost certainly did not take into account an expected 20% or so change in the price level in the course of two years. More of these people than currently expected may begin to return to work.

The bigger labour supply problem of a rise in chronic sickness is sadly one that will respond less to economic incentives.

The OBR

I’m a bit worried about the Office for Budget Responsibility. I think over the last 12 years it has become a useful part of the British macro-setup. And now it risks being side-lined.

From 2010 until 2020 the accepted approach was that major fiscal announcements happened twice a year and each came alongside an OBR medium term forecast and policy costing document. The numbers, the assumptions and the likely economic impacts were transparent. And whilst people could disagree with the OBR (I certainly believed their capital spending multipliers in the early 2010s looked far too small) there was at least a common starting point for analysis and a baseline set of numbers for the debate to work around.

That system broke down in 2020. As Chancellor, Rishi Sunak was forced to change policy in response to the pandemic every 6-8 weeks. That was understandable. Process should not delay policy in an emergency.

Less understandable is the newer trend of having major fiscal events which are budgets in all but name without OBR numbers. Last September saw a major announcement on tax rises, social care and NHS funding without any OBR numbers. May’s cost-of-living plan was essentially another budget but one without an update in the forecasts.

And next month it will happen again. Liz Truss wants an emergency budget in September. It will no doubt be called ‘an emergency budget’ but not be an ‘official’ budget complete with OBR documentation. They simply don’t have the time to carry out the necessary work.

I was struck by a Truss line in a recent FT interview:

Truss said that, if elected, she would hold a Budget “straightaway” and reverse the entire planned corporation tax increase, a move that will blow a £17bn hole in the public finances. The foreign secretary insisted she could afford tax cuts costing more than £30bn by using up “headroom” in current fiscal forecasts — even though economists believe a sharp economic downturn could wipe this out. Truss refused to discuss the “hypothetical” situation of the headroom disappearing, but insisted she would not let borrowing soar.

The situation is far from hypothetical. It is based on OBR forecasts from March that do not take into account the spike in global energy prices that began in February, do not account for May’s support package - that will have to be rolled forward in some form - or the expected rise in unemployment as growth slows.

But we likely won’t know what the OBR thinks the ‘headroom’ actually is until some point in November or December - when we have an official fiscal event - some months after another fiscal policy intervention.

Using out of date information to set policy seems far from ideal.

Thanks for reading Value Added. It is a subscriber funded publication. If you’re enjoying it please do consider taking out a subscription. You’ll get more posts and I’ll get the resources to carry on writing it.