What were central banks supposed to do?

Inflation is uncomfortably high. But central banks faced a tough trade-off.

I almost feel sorry for central bankers. For a decade or so after 2009 inflation mostly undershot their targets. Policy-related academic macro working papers bewailed their inability to generate inflationary pressure. There was an active debate on whether generating higher inflation would require changed targets (average inflation targeting, price levels targets and the rest) or new tools. That though is now all forgotten.

As inflation has climbed to uncomfortable levels the very same institutions that were once berated for their inability to generate inflation are now being slammed for allowing it to be too high.

This week’s Economist doesn’t pull its punches.

That said, whilst the accompanying leader will not make for fun reading over at the Fed, I’m a touch unclear exactly what it is advocating1.

It notes that rates in the US might have to raise to the 5-6% range to quell inflation, probably causing a recession:

The usual way to rein in inflation is to raise rates above their neutral level—thought to be about 2-3%—by more than the rise in underlying inflation. That points to a federal-funds rate of 5-6%, unseen since 2007.

Rates that high would tame rising prices—but by engineering a recession. In the past 60 years the Fed has on only three occasions managed significantly to slow America’s economy without causing a downturn. It has never done so having let inflation rise as high as it is today.

But doesn’t quite go as far as advocating that. It all feels a touch like the advice to the tourist asking for directions and being unhelpfully informed ‘I wouldn’t start from here’.

I would also rather inflation was not as high as it currently is. But I’m equally clear that hiking rates to 5-6% would be a mistake.

Over at the Telegraph, Jeremy Warner is as angry at the Bank of England as the Economist is at the Fed. And on much the same grounds. How did they get it so wrong he asks?

I’m left wondering what the supposedly better counterfactual looks like?

If the Monetary Policy Committee had had perfect knowledge of how the last 18 months would play out, what exactly were they supposed to do differently?

Presumably raise rates at a faster pace.

The problem of course that a high Bank Rate would not have eased the energy crisis, prevented the Covid-related supply chain disruption which is hitting global value chains nor really eased the post-pandemic reshaping of household consumption patterns away from services and towards goods.

A Britain in which the Bank had begun to aggressively hike 18 months or so ago towards the kind of levels able to generate enough domestic disinflation to counteract global inflationary pressure is one where CPI inflation might indeed be closer to 3.5-4% than 7%. But it is also a Britain where the employment rate is lower, unemployment is higher, wage growth materially slower and GDP growth barely positive.

I struggle to conclude it would be a better outcome.

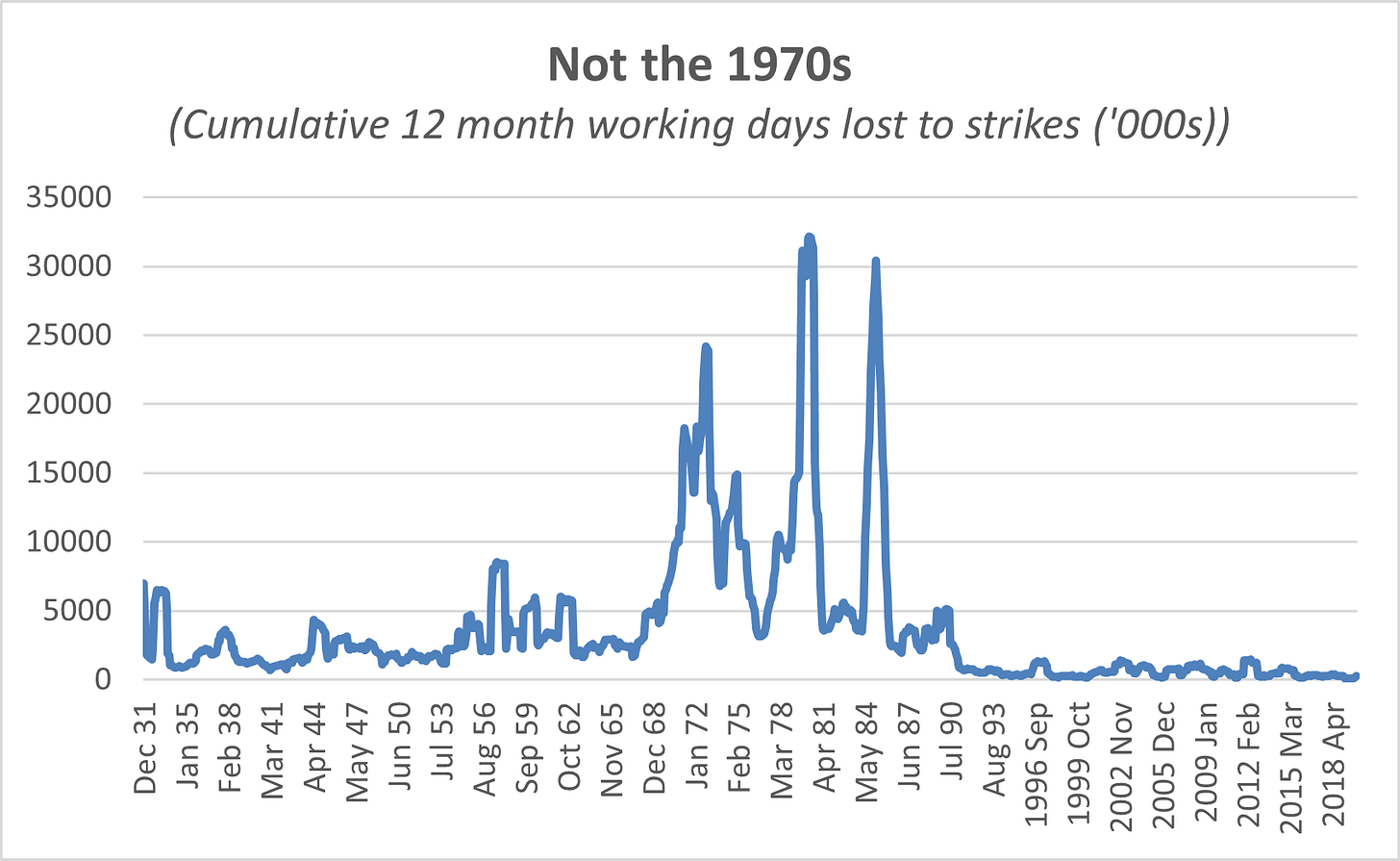

Nor do I believe that the current outlook is anything like the 1970s. Chris Giles, in his column at the FT, worries that policymakers must ‘relearn’ the lessons of that decade.

He writes that US and UK inflation is, just as in the 1970s, the result of both global cost-push and domestic demand-pull factors.

Whilst I don’t disagree on the global cost-push side (although it is worth keeping in mind how less energy intensive GDP is than in the 1970s), I worry about the domestic demand-pull argument, at least in the UK.

The labour market of the 2020s is radically different to the labour market of the 1970s. So different in fact that any comparison has to be treated with extreme caution.

As Chris writes:

In the UK, the latest labour market figures this week showed an unemployment rate of 3.8 per cent, the lowest since 1973, an all-time record for the number of job vacancies. Total pay rose annually by 5.4 per cent.

Sure. But in 1973 when headline unemployment was last this low, nominal wage growth was running at over 14%.

In other words what matters as a driver of wage growth is not so much the rate of inflation or some nebulous idea of inflation expectations but the overall health of the jobs market and the wider economy. And with a liberalised and flexible jobs market, as Britain has, it has to get very tight indeed before it generates sustained high earnings growth.

Union density is now around 20% and about one in four workers have their terms, conditions and wages set by collective agreements. As late as 1980 union density was over 50% and collective bargaining coverage around 70%.

And then there’s this:

I began this piece by saying that I ‘almost’ feel sorry for central bankers. The ‘almost’ is important.

The first story runs something like this and is rooted in structural changes in the shape of the macroeconomy, the supply side and changing political economy:

Beginning in the 1980s the structural bargaining power of labour was reduced a period of high unemployment following tight macro policy, by a breaking of trade union power and by the further liberalisation of the jobs market. The end of the cold war, the entry of China into the global economy and the globalisation of supply chains from the late 1980s into the 1990s supercharged these trends. The pool of labour available to Western capital almost doubled in the space of two decades. Meanwhile advanced economies became less energy-intensive. The result of less feedthrough from energy price spikes and lower goods prices due to globalisation was reduced headline inflation and lower volatility of inflation. Weaker labour bargaining power ruled out the kind of wage-price spirals which had bedevilled policymakers in the past and helped to keep services inflation low and stable.

Or one can tell a very different story, one rooted in inflation expectations and credibility. This one goes something like this:

Inflation was high and volatile in the past because macro-policy was ineffective. Monetary policy was too subject to political whims and fiscal dominance. Fiscal policy was often firmly set to manage a political business cycle (easier before elections and then overcompensating afterwards) rather than an economic one. Firms, workers and investors came to expect that policymakers would lack the resolve to tackle inflation so they set prices and wages ever higher. The solution was credible, independent central banks with a mandate to keep inflation low. These banks demonstrated their credibility by keeping policy tight to drive down inflation, even at a high cost in terms of joblessness. By the mid-1990s that hard-won credibility had helped to anchor inflation expectations. Now that firms, workers and investors had a clear view of the reaction function of central banks in the face of rising inflation they expected inflation to remain and low and stable and so set prices and wages on that basis.

Both stories contain elements of truth. But central bankers spent the 1990s and early 2000s talking up the second. If you claimed too much credit for the low inflation of the 1990s and 2000s then you can reasonably expect to take too much of the blame for the high inflation of the early 2020s.

Central banking is more akin to sailing than driving. Whilst it might be tempting to imagine them steering the economy with a reliable accelerator and brake, they are far more at the mercy of the elements. They can tack and trim with a greater or lesser degree of skill, but in the end they can’t change the wind.

If you’re enjoying Value Added – please do subscribe. You’ll get more posts and I’ll get the resources to carry on producing them.

I have yet to read the accompanying Special Report – but it looks excellent.