What's in the price?

In 2007-09, financial developments drove the economic cycle. This time they are reacting to it.

A useful thing to remember when reading almost any financial journalism is that if you try hard enough, you can always find someone willing to make a dire prediction. Indeed, you don’t really have to try very hard at all. Some people just like seeing their name in the papers and have worked out exactly what quotes will hit the right buttons.

So, it’s always worth reading any grim set of prognoses with a pinch or two of salt. No matter how eminent the herald of doom may appear. In 2010 Bill Gross, then still widely known as a ‘bond king’, made a splash with a warning that UK government debt ‘rested on a bed of nitroglycerine’. There a followed a decade in which the yield on gilts continued to hit new lows. The UK faced many problems in the 2010s. Funding its debt stock was not one of them.

This week will no doubt see a lot of pieces peppered with warnings of some form of financial apocalypse if Liz Truss proceeds with her plans to ramp up government borrowing and cut taxes in the months ahead.

The best course of action is to look at what markets do rather than listening to what those who work around them say.

The case for getting jittery is straight forward. August was a bad month for both sterling and the gilt market. Andy Bruce’s chart is not something old Treasury hands will want to dismiss.

The reason this chart provokes so much fretting is that, in general, sterling should not be falling whilst yields are rising. Higher yields on sterling assets should attract inflows and help prop up the exchange rate. If you are so inclined, you can certainly take this numbers and spin a yarn of markets losing faith in the UK.

But, as ever, you can use data to tell several different stories.

Sterling/dollar is going to be an important measure to watch in the months ahead. With most global energy priced in dollars then any weakness there magnifies the impact of the shock Britain is feeling. Indeed the case for paying more attention to sterling/dollar than is normal is strong. But any bilateral exchange rate – by definition – is impacted by developments in both countries. The pound is indeed falling against the dollar – but so to is the Euro (subscribers can expect a wider post on this later in the week).

I, in general, prefer to look at the Bank of England’s broader index of sterling rather than any single cross rate. It gives a sense of the bigger picture.

The picture here is more nuanced. August still looks grim with a fall of almost 4% in the value of the pound since late July. But the broader picture is of sterling well within its post-2016 – and indeed post-2008 – trading range. The broader sterling picture is of a flashing amber warning light rather than a red one. This is an indictor worth keeping an eye on in the months ahead.

The move in gilt (British government debt) yields is harder to explain away with a wider cross-country look. The yield on a ten year gilt has risen by 92 basis points over the last month (and to clarify, yes that is a big move). By contrast the equivalent yields in Germany and France have risen by 62 basic points and 75 basis points. Whilst there was been broad pressure across European government debt markets, Britain is feeling the squeeze more than some peers.

That is uncomfortable for an incoming government which will be looking to ramp-up issuance of new debt in the months ahead but mostly reflects market expectations of higher interest rates/tighter monetary policy in the coming quarters rather than any fears of declining British government credit quality (as some of the more excitable talking heads are already claiming).

One doesn’t need to be talking up a financial implosion to be deeply worried about the UK outlook. And certainly there is a rising sense of nervousness among market participants than stretches well beyond the roll call of the usual doom mongering suspects. But it is a fear, rightly, rooted in economic rather than financial developments.

The UK faces an economic crisis rather than a financial one. A negative terms of trade shock coming on the back of an economy still disrupted by the pandemic and after more than a decade of insipid GDP, productivity and wage growth is going to be extremely painful. Inflation is running at a 40 year high and real incomes are set to experience their steepest fall in decades.

I fear that the incoming Truss government is about to make this macroeconomic problem worse with overly expansionary fiscal policy1. An energy price bailout for households and firms on the scale of the furlough scheme is needed. Adding discretionary cuts in corporation tax, national insurance contributions and perhaps income tax and VAT on top of that – at a time when the supply side of the economy is seriously constrained – feels like an unnecessary gamble, a stoking up of demand at almost exactly the wrong point in the cycle. It will lead to inflation being higher, for longer.

The case against circa-£30bn+ of discretionary tax cuts at this stage – even when combined with an energy price bailout costing perhaps 3x as much - is not that it will ‘bankrupt Britain’ or, and I have now heard this take in the wild now, lead ‘to a 1976-style IMF bailout’. It’s far more mundane than that. It’s that in the short run of the next 18-24 months or so tax cuts will add more to inflation than growth - and push interest rates higher. For most households the temporary boost to take-home pay from lower taxation will be quickly swallowed up by faster price rises and higher interest rates.

For the British government itself, the risks to mistiming a fiscal giveaway are not that rates soar to a level where funding government debt becomes impossible but rather to a level which is merely deeply unpleasant.

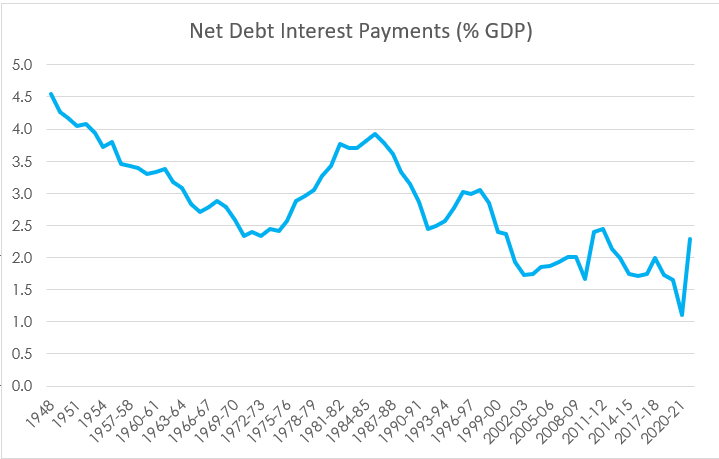

For all the build up in government debt levels since 2008, the actual burden of debt service in Britain has been historically low.

The fall in interest rates since 2008 has been, in macro terms, a much bigger deal than the rise in debt levels. Excessive fiscal easing now could prove doubly damaging in that it both raises the level of debt to GDP and in that it pushes the rate of interest on that debt higher.

A debt burden, in terms of servicing costs as a percentage of GDP, more akin to that of early 1980s than that of the 2000s or 2010s looks increasingly likely.

My read on the UK market price action is that this is the sort of messy outcome that is being increasingly priced in. A supply shock has left Britain with an inflation problem and government policy looks set to make it worse. That means higher interest rates than almost expected just twelve months ago. Markets are adjusting to that reality. In 2007-09 financial developments drove the economic cycle. This time they are merely reacting to real changes in the economy. The economic outlook looks grim and pricing is simply reflecting that.

Thanks for reading Value Added. It is a subscriber funded publication. If you’re enjoying it please do consider taking out a subscription. You’ll get more posts and I’ll get the resources to carry on writing it.

Now there’s a sentence I haven’t had to write about the UK in a very long time.